by Matt Robinson

Since Hurricane Andrew hit North Carolina in 1992, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has relied on portable housing units to provide temporary shelter for survivors of natural catastrophe. As recently as 2008, when Hurricanes Ike and Gustav pummeled the Texas and Louisiana coasts, FEMA deployed thousands of temporary housing units (THUs), manufactured structures designed for short-term occupancy, to assist displaced populations in their return home.

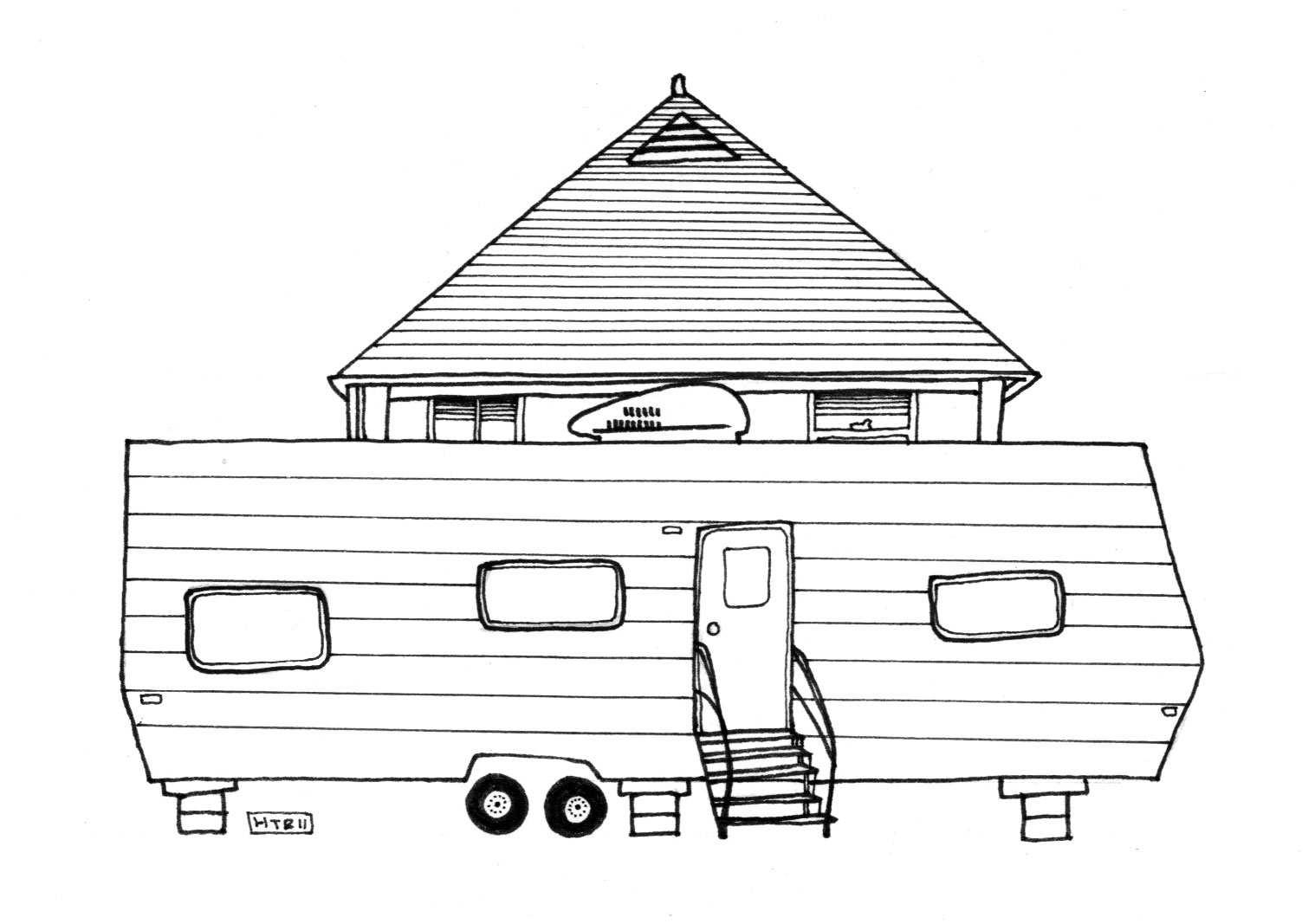

Most infamously, FEMA also relied on manufactured housing after the record-breaking storm season of 2005. To provide shelter to tens of thousands of displaced families, FEMA cobbled together a fleet of 150,000 mobile homes, park-model “Katrina Cottages,” and travel trailers, commercial campers designed for use off-the-grid. The units were sent throughout the region.

Thousands of mobile homes were never used, though, due to federal flood-plain regulations, and the Katrina Cottage program was slow to get off the ground, so the bulk of THUs provided for the 2005 housing mission were travel trailers, bought off dealer lots at first but later built to FEMA specifications under manufacturer contracts.

Almost as soon as the shelters reached disaster zones the trailers became a public health nightmare and a threat to the very occupants the program was meant to serve. Children in the trailers began to suffer an odd array of symptoms, from headaches to nosebleeds, and allergies developed in children and adults alike to household and dietary products that had never been a problem before. Hair spray, disinfectant, processed foods, food with red-dye coloration, and a host of other innocuous things suddenly triggered allergic reactions among families seeking refuge in the trailers. As reports of sick families mounted, FEMA field agents tried to assess the problem and, largely due to the work of the Mississippi Sierra Club, formaldehyde was identified as the likely source of illness.

Almost as soon as the shelters reached disaster zones the trailers became a public health nightmare and a threat to the very occupants the program was meant to serve. Children in the trailers began to suffer an odd array of symptoms, from headaches to nosebleeds, and allergies developed in children and adults alike to household and dietary products that had never been a problem before. Hair spray, disinfectant, processed foods, food with red-dye coloration, and a host of other innocuous things suddenly triggered allergic reactions among families seeking refuge in the trailers. As reports of sick families mounted, FEMA field agents tried to assess the problem and, largely due to the work of the Mississippi Sierra Club, formaldehyde was identified as the likely source of illness.

Added to this was the frightening number of fires and explosions that destroyed the units and injured or killed occupants. In the first two years of trailer use, scarcely a month passed without one or two electrical fires or propane-related explosions somewhere along the Gulf Coast, causing injury or death, destroying whatever property had been salvaged from the storms, and bringing even more grief to survivors.

FEMA’s response to these problems was first to deny the problem of formaldehyde exposure by ordering field agents to cease their efforts to get to the bottom of the developing crisis. Second, the agency attempted to bureaucratically disown the situation through a year and a half of foot-dragging. When the toxic exposure continued to be

reported, the agency ordered a study of indoor air quality– at the behest of an outraged Congressional committee that revealed FEMA’s duplicity in the matter through internal emails. When released, the study was roundly criticized by an array of doctors and scientists who questioned its sloppy methodologies and the conclusions it drew.

Further studies confirmed elevated levels of formaldehyde fumes found in almost every type of trailer. Ultimately, a series of lawsuits against manufacturers was resolved mostly in the manufacturers’ favor, despite well-documented evidence of the dangers occupants faced. Explosions and fires caused by a combination of occupant unfamiliarity with the units and poor-to-no maintenance of the leaky structures continued into 2008. Investigators found evidence of faulty installations and improper servicing of the units. Specialized electric wiring and propane systems were often overlooked by contractors with little to no experience in travel trailer upkeep. Initially, four major engineering firms – the Shaw Group, Fluor, CH2MHill, and Bechtel – were tasked with the installation and maintenance of the trailers, but when smaller local businesses loudly complained about the no-bid contracting process, FEMA relented and handed out contracts to three dozen small businesses.

Not all were equal to the task. Politically connected companies, including one owned by Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour’s niece, received contracts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars despite their lack of expertise, as did janitorial service providers, a roofing repair company, an accounting firm, and even a scuba-diving business. The results were seen in plumes of smoke and the charred remains of the boxy units that littered neighborhoods of New Orleans and many other places from Texas to Florida. Several of these companies have been investigated and found guilty of fraud in their actions. More trials are yet to come.

FEMA would argue today that the agency learned from its mistakes in the 2005 recovery. Limits on formaldehyde levels were put in place, and now all units approved for use have, theoretically at least, levels of the chemical not thought to pose a threat to occupant health.

FEMA also banned the use of propane in its THUs, and demanded that electric systems be upgraded to household current, rather than using 12-volt battery systems traditionally installed for off-the-grid use. Units issued for emergency housing in recent years are largely designed for handicap-accessibility, and are the larger park-model type trailers rather than the notoriously cramped travel trailers.

FEMA’s contracting procedures for emergency housing have improved since 2005, but the agency hasn’t had to meet the same scale of challenges since. The hundreds of thousands of Americans at risk in dozens of vulnerable cities across the country can only hope that these lessons of the past have been taken to heart.

Share