by Umang Kumar

In 2010, we watched with disbelief the British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil-leak disaster unfold before our eyes in the Gulf of Mexico. We saw how BP tried to minimize any negative coverage of the incident and how the media continually carried their reports. We saw the emotions of the Gulf Coast residents weighing the effects of oil washing to their shores. In light of the pollution caused by BP, it seemed more restrictive regulations were being contemplated on the oil economy which undergirds much of that area.

In 2010, we watched with disbelief the British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil-leak disaster unfold before our eyes in the Gulf of Mexico. We saw how BP tried to minimize any negative coverage of the incident and how the media continually carried their reports. We saw the emotions of the Gulf Coast residents weighing the effects of oil washing to their shores. In light of the pollution caused by BP, it seemed more restrictive regulations were being contemplated on the oil economy which undergirds much of that area.

But not to worry– despite some speculation as to whether BP might “go under” because of the incident, it reported $7.7 billion in profit for the fourth quarter of 2011, a 38 percent increase from a year earlier. While ordinary people are often cast onto the streets when some disaster strikes them – a storm, an illness, a foreclosure or business loss – corporations seem to know the logic of survival and flourishing much better than we ordinary folk.

A similar story of industrial negligence, evasion of responsibility, a campaign of disinformation and an exercise of corporate power has been the experience of the survivors of the Bhopal gas disaster in central India since 1984. The question is, how does one keep re-framing what happened 28-years ago and has continued happening since? How does one keep bringing up, even to oneself, the question of Bhopal?

On the 2nd of December 1984, over 40 tons of Methyl Isocyanate gas (MIC) leaked from a plant owned by the multinational corporation Union Carbide, in Bhopal in central India. Some call it an “accident,” others the inevitable result of a culture of negligence, an entirely preventable tragedy. That night several thousand people perished, most in a very painful manner, poisoned, frothing at the mouth, with burning eyes and with no idea what was happening to them.

The gas leak killed over 10,000 people in the three days following the disaster. Survivors exposed to the gas on that day continue to be plagued with health problems like respiratory issues, cancers and congenital malformations in their children.

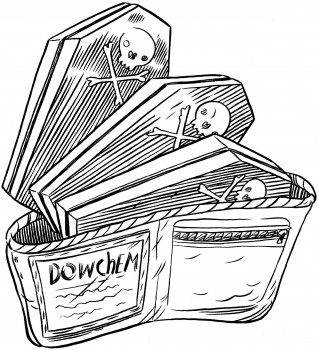

It is an ongoing disaster. The site has not been cleaned up, which has resulted in contamination of the ground water, the only source of drinking water for several communities close to the area. The victims of the disaster are yet to receive just compensation from Union Carbide or the current owner, Dow Chemical Corporation. For the survivors, the Bhopal disaster did not end that night, but has been a continuing nightmare for the last 28 years.

I think it will be fit to reproduce what the website of a clinic set up for survivors – the Bhopal Medical Appeal site which chronicles the activities of the Sambhavana Clinic in Bhopal – has to say about the continuing tragedy in Bhopal:

“Many are unaware that the disaster in Bhopal continues to this day. An estimated 120,000–150,000 survivors of the disaster are still chronically ill. Over 25,000 have died of exposure-related illnesses and more are dying still. Tens of thousands of children born after the disaster suffer from growth problems and many women suffer from menstrual and gynecological disorders. TB is several times more prevalent in the gas-affected population and many forms of cancers are on the rise.”

What is also a fact, often under-reported, is that a majority of the victims and survivors were from the lowest rungs of the society. Just as many find themselves living in the shadows of Louisiana’s refineries and chemical plants, those most immediately affected by the Bhopal gas were those living in slums around the factory. As the editorial in the Bhopal Marathon e-magazine titled “The Bhopal Marathon: An ordeal of pain measured not in miles but in years,” puts it, “For almost thirty years now, some of the poorest people on earth…have been fighting for their lives and fundamental human rights against a multinational giant backed by governments and economic elites of two powerful nations.”

In contrast to the multinational giant and its resources, the editorial goes on to characterize the survivors as the “nothing people,” who “have literally nothing.” It is perhaps not insignificant that these “nothing people” are literally those whose lives can be ignored and kept at the margins – and left to fend for themselves for 28 years now.

In a convoluted and devious case of chicanery, financial sleight-of-hand and legalese, the corporations which have been players in this tragedy – the U.S.-based Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) and its Indian subsidiary, Union Carbide of India Limited (UCIL) and then Dow Chemical Corporation which took over UCC in 2001 – have tried various ways to avoid any responsibility.

Some of their tactics of deceit and delay are not unlike those used by Exxon to avoid responsibility for the Exxon Valdez spill: dragging out legal proceedings for decades until those affected have given up in despair or died. This shirking of responsibility and the efforts to disassociate themselves from the incident fall in line with how corporations – and the systems of government power they are in symbiotic relationships with – shield one another and find ways to wiggle out of any culpability. In addition, there is no attempt at remorse, at detailed failure-analysis, at a transparent sharing of information to find ways at remediation. Instead, what one observes are all manner of attempts at secrecy and the hiding of information.

In the Bhopal case, there was evidence of poor design, cutting corners in plant maintenance and lower safety-standards in the UCC plant in Bhopal much before the leak. After the gas leak, UCC tried to pin the blame on “saboteurs,” but was never able to name any one person. More seriously, in the immediate aftermath of the incident, UCC refused to release the formula of MIC, which could have helped the doctors in coming up with antidotes – it cited trademark concerns! We see this echoed in Nalco’s refusal to publicize the recipe of the toxic dispersant “Corexit” used in the Gulf.

The struggle for compensation to all Bhopal survivors and the dead was another case-in-point of a corporation strong-arming its way through fair proceedings. As recent investigations have revealed, UCC, the perpetrator itself, decided on injury categories and compensation amounts for the survivors. It used Indian Railway Act tables to determine compensation for the deceased. As a result, “[i]ts definition of temporary injury covered 94% of the victims, nearly all of whom were people with injuries that lasted all their lives. They were to be awarded $494.” In court, UCC’s lawyer argued that some of the victims had prior conditions of TB and other lung diseases and thus “[e]ach individual history has to be examined…”

Is this not similar to how BP hired Kenneth Feinberg to decide who of those affected deserved settlements or payouts, and how BP denies and puts off responsibilities for the many ill health effects of the oil and dispersants? The quotes could as easily have come from BP’s lawyers.

Not just that, but after agreeing to have the case adjudicated in India, UCC refused the court summons when criminal proceedings were re-instituted against them in 1991 by the Indian Supreme Court. The subsequent sale of UCC’s nearly 51% stock as parent company in the factory to an Indian company in 1994, and later its being bought by Dow Chemical Corporation in 2001, have only served to further obfuscate matters behind contrived legal frameworks.

Dow seems to think it has moved past this ongoing tragedy, much as BP’s advertising tries to say the clean-up of the Gulf is done and complete. The distancing effected by the procedures of sale of companies is supposed to be so watertight that Andrew Liveris, the current CEO of Dow almost touchingly observed, “the notion that you acquire a company where… the liability that was settled way beyond your time, and to hook you into that event, it’s beyond belief that people are still trying.”

To the survivors of the Bhopal incident and their supporters, culpability has never been a contentious issue. They have seen how at every step the deep-pocketed corporations have sought to shirk their responsibility and have resorted to endless tactics to stonewall any proceedings towards a fair outcome. The survivors have meanwhile persisted in their efforts, never giving up hope and taking every opportunity to oppose the propaganda by the guilty– the recent effort to oppose Dow Chemical’s sponsorship at the London Olympics was an example. Earlier in 2011, survivors marched on foot all 470 miles from Bhopal to the capital New Delhi to press their demands: the creation of a national commission with adequate local representation and funds to provide needed healthcare facilities, formation of a CBI special cell (like the FBI) for speedy prosecution of UCC’s chief Warren Anderson and other accused in the criminal case, and a scientific assessment of the depth and spread of toxic contamination due to chemical waste stored at the factory premises.

In their long-drawn out struggle, the Bhopalis (a shorthand here to refer to the people of Bhopal struggle) have acutely been aware of solidarity with several other struggles around the world. The BP oil-leak saga was keenly followed as another battle between common people and a giant corporation that has been involved in “green-washing” activities for a long time.

The sheer clout of BP, the ambiguity of the stance of the U.S. government all along, despite the pretending to hold BP responsible, and the way the people affected were treated as almost irrelevant– none of this was lost on the Bhopalis. To their minds, this has been an instance which suggests solidarity and joining forces, to carry on the struggle against these injustices, long after so-called disasters are “sealed” and “closed” by some token compensations or settlements.

The two struggles can exchange information on medical symptoms and analysis of harmful chemical effects that the mainstream channels will not acknowledge in incidents like these – the Sambhavana clinic in Bhopal has been a model institution providing free treatment to survivors of Bhopal and also carrying out its own analysis of the ailments that persist long-term. The two struggles should also join hands in corporate boycotts and in blowing the lid off all efforts at disinformation, especially the projection of angelic fronts by means of green-washing. For instance, the efforts of the “Yes Men” films in exploding myths of the corporations involved in the Bhopal case has had wide appeal and impact. E-mails obtained by Wikileaks last year show that Dow paid great sums to investigative companies to carefully monitor and track even the most minute actions of Bhopal activists, including the Yes Men. There is no reason to think BP would not do likewise.

Speaking tours by affected people also can create greater common understandings, and help those not directly affected understand that they could as easily be mistreated. In the end, we should recognize that across oceans and landmasses, across cultural and geographic distances that separate our struggles, what we are up against has much in common. For our own good we must learn from each other, and look to one another, locally and globally, for needed strength and inspiration.

Umang Kumar is a volunteer with the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal (ICJB).

Share