By: some anarchists from the Milneburg Hall occupation

In the still hours before dawn on September 1st, 2010, hidden from patrolling UNO police by a cover of darkness, we trudged in disjointed groups across the campus of the University of New Orleans. As our small band crouched behind the shrubbery lining Milneburg Hall, one of our comrades emerged from their overnight hideout in the building’s computer lab to grant us free reign over our new dominion.

And so began the first phase of our plan of action.

Once inside, we set about collecting large objects with which we could secure all four sets of ground-floor doors. Hauling tables and desks from nearby, and even from the second floor using the elevator, we employed a makeshift barricade in front of the doors. With a table laid sideways across the door jamb, the idea was to then tie the handle to the table, effectively rendering the door unusable from not only the inside, but more importantly from any outside tugging.

This, however, required some wrangling. If the cops could tug even an inch of leeway, they would be able—in theory—to cut the rope of the truck tie downs and pull the door open. Now, we all know cops are not the sharpest tools in the shed, but we weren’t taking any chances. In retrospect, considering none of us had ever before fortified a barricade, a dry-run would have probably proved a good idea. As the nighttime UNO police car made the rounds in the distance, we fought with the first door for more than 20 precious minutes, to no avail. We soon realized that the step-by step instructions for locking down this particular kind of door in our manual, “Occupation: A DIY Guide”, was essentially inaccurate, and we would need to pioneer a new method.

After many flustered minutes at a loss for how to proceed, we finally developed a technique. A couple of us wedged the table just beneath the doors’ push bars, as Mouse and Apoc dutifully wrapped the truck tie downs around and around the bar’s frame, then clamped the tie downs as tightly as possible around the table until it wouldn’t budge. One push on the door, and it was clear we had successfully sealed off that entrance. With this initial lockdown complete, it didn’t take long to repeat the process on the rest of the doors.

A light began to rise out of the dark sky as we barricaded the last of the doors. And timing was critical: only minutes after we were confident the building was ours, a janitor strolled up to begin his workday, a little before 6am. To make our intentions clear and waylay any confusion, we had taped handwritten signs to the glass doors reading, “THIS IS A STUDENT OCCUPATION IN PROTEST OF THE BUDGET CUTS.” If not supportive, he at least showed no hostility toward us. After all, the janitors were being laid off due to these very budget cuts. Before he shuffled away, Morpheus asked, “If you could not tell the cops for another 30 minutes or so, that would be really helpful.” Media press releases would be sent off within the hour, and we were counting on the arrival of students to offer support—lest the cops break in prematurely and arrest us.

The UNO PD did grow privy to our operation soon enough, however. They first tried unlocking the doors, followed by more forceful tugging. When both failed (success!), they focused their efforts on wearing down the human element.”Open the door, man,” a lone cop pleaded to Morpheus, whose face was partially covered by a bandana. “We need to talk about this.”

The UNO PD did grow privy to our operation soon enough, however. They first tried unlocking the doors, followed by more forceful tugging. When both failed (success!), they focused their efforts on wearing down the human element.”Open the door, man,” a lone cop pleaded to Morpheus, whose face was partially covered by a bandana. “We need to talk about this.”

“We can talk through the glass,” Morpheus replied.

“You guys need to open this door, or they’re gonna call the SWAT to break in. It’s gon’ be bad, man.”

“Students have been doing actions like this all over California—”

“This is not California, man!” He was emphatic. “They gon’ tear gas this building, send their dogs in, and arrest all y’all! This is a felony offense. It’s gon’ be bad, man. I’m beggin’ you. This is your future, man.” He even offered to come in alone and unarmed if we opened the door! Regrouping on the second floor minutes later, we weighed the possibility of the threats of the UNO PD, while fiendishly texting comrades to offer ground support as soon as possible. Although well versed in the manipulative, fear-inducing tactics employed by the cops, the New Orleans police are particularly volatile, and we discussed the implications of the SWAT team being called.

Well, for the time being, the university building we held was our autonomous zone, and whatever consequences arose from our actions, we were all in it together. If only for a few hours, we were warriors, brave and free. Imminent arrest may have lay just ahead, but victory is in every step of a process, even the attempt. So we celebrated—with ice cream sandwiches and soymilk from the teacher’s lounge!

Two weeks earlier, in response to the severity of the budget cuts being steadily implemented since the Wall Street financial crisis of 2008, we decided the 2010 school year needed to be brought in with a bang. A call was put out to students and local activists for a walk out of all classes on the morning of September 1st to demand the UNO administration cease conceding to the needs of a capitalism in crisis at the expense of their students, faculty, and staff.

Two student organizers approached the members of the Save UNO Coalition, the primary organizing body on campus against the cuts, to entreat their support for the planned walk out. Save UNO was less than enthusiastic, however.

Two student organizers approached the members of the Save UNO Coalition, the primary organizing body on campus against the cuts, to entreat their support for the planned walk out. Save UNO was less than enthusiastic, however.

This group was comprised of the faculty who studied social struggle for a living. They paid lip service to the tactics of civil disobedience used during the Civil Rights movement, but what of this new student struggle, not yet analyzed or deemed worthy for the annals of academic Leftism? In the face of a university in shambles—with janitors being laid off, with their own jobs in jeopardy, with whole majors and departments going the way of the dinosaur—the Save UNO “coalition” denounced our confrontational plan for a student strike as “ill-timed.” They preferred a course of action not contingent upon consistent conflict, but rather, through less protest-oriented events in hopes of gaining support from the commuter-campus masses before any bigger demonstration could be staged. After shelving the notion of supporting us and thirty minutes of meeting time spent discussing when their next meeting would be, someone unaffiliated with our group piped up, “So what are we meeting about?

At this, members of Save UNO quickly decided on plans for a massive protest…in March, six whole months away! Better, we decided, to act now; even if it alienated a portion of the student body, we could at least connect with those ready to fight to reverse the spiral down which the university was headed as a result of capitalist injustice. Why wait?!

Despite being deflated by our purported allies refusing to lend support, we resolved to organize popular support ourselves in the two weeks leading up. Undeterred, we went ahead with our plans…

We also had a trick up our sleeve. Though busy enough preparing for the scheduled walk-out, we knew the element of surprise could capture the attention of both the students and administration like none other. Inspired by the budding student-occupation movement in New York and California, where students by the dozens seized buildings in protest of budget cuts, we too decided such a subversive measure was in order for UNO. An action that would shatter the passivity of symbolic protest, physically empowering the strikers: a takeover of Milneburg Hall!

A few of us would enter in the night, lock down the Social Sciences building, and cause an uproar on campus, thus gaining more support for the scheduled walk-out later that morning; then, once a critical mass had assembled outside, we would open a door to flood Milneburg Hall with students for an “open occupation,” with us initial occupiers blending in with the surging mass. And then we’d throw a dance party!

But all didn’t go according to plan…

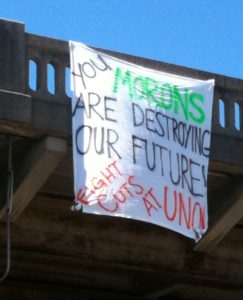

“This building is under the occupation of its students! Who dat?!” yelled Trinity through the megaphone out the window of the third floor to a cluster of excited students below. We had decorated the chalk boards with slogans reading “Class Cuts? Class War!” and “Occupy Everything!”, as we ran wildly through the halls. Meanwhile, a fearless Dozer climbed out the window onto the ledge of the building’s facade to, like the besieging of a castle, unfurl our three banners proclaiming our platform: “OCCUPY. STRIKE. RESIST.”

“Don’t do that, man,” the cop from earlier advised, while Dozer tied the corner of first banner to the cement column. “Don’t go around that, man,” he continued, as Dozer slipped around the column to the next ledge, the crowd looking on from below. At this point, such pleading was a consolation for the cops who held absolutely no power over the unwieldy situation. But with more people arriving by the minute, and calls pouring in from reporters trying to confirm the building occupation, it was all the UNO PD could do to keep the media frenzy at bay, as they told them that reports of a student uprising were all false.

So far all was going according to plan. We were biding our time as the hour of the scheduled walk-out loomed closer and closer, and more assembled outside Milneburg. A few of our comrades outside were in the midst of riling up students in anticipation for what was to come. If we held one aspiration for our action it was enticing the student body to join in, escalating the fight, and leveraging our collective power. At 10am, we would relinquish a barricade and bring our occupation zone from a modest few up to more than a hundred! A full-blown open occupation to fracture the violent continuum of “business as usual” calmly overseeing UNO’s deterioration.

But at approximately 9am, things went horribly awry.

But at approximately 9am, things went horribly awry.

“They’re in!” yelled Tank, who had been on ground-floor watch. Unfortunately, we had missed a detail in our late-night reconnaissance: a partially open ground floor window on the side of the building. Next thing we knew, like the Sentinels breaching the hull of the Nebuchadnezzer, a squadron of cops flooded our rebel fortress through an interior door off to the side, drawing guns and even placing one of our numbers in handcuffs! As we frantically called to one another, the cops followed closely behind.

The UNO police chief suddenly broke in to order his goons to put their guns away and unlock the handcuffs. As we followed him downstairs, he said he wished to negotiate with us. We saw police lining the foyer, one of wooden folding tables split in half in their efforts to unlock the door, as spectators squinted into the glass. At this point we knew the jig was up and were positive we were getting a free ride to Orleans Parish Prison. Though suspicious, we agreed to “negotiate.”

We were led into an auditorium, and Chief Harrington ordered the other cops from the room. After calling in the university provost, Joe King, what commenced was a half-hour meeting, videotaped by one of the occupiers (which can be viewed on YouTube under “UNO Occupier Speak to Provost Joe King”). The meeting was essentially useless, but one piece of information we learned was that not only was UNO PD bluffing on their threats to call upon the forces of the SWAT team, they were incredibly relieved to not have had to resort to such a measure, as it would have proved highly unfavorable to the image of the university. Thus, we held more leverage than we had first thought. When Chief Harrington chided us (quite humorously, we might add) not to use bandanas in the future to conceal our faces because it is “an anarchy sign,” one of us retorted, “Well, we weren’t necessarily planning on getting arrested.” Although the day’s events were surreal enough, the chief’s next statement came as the greatest shock of all: Not only did he harbor no intentions to arrest us, but he wanted to help us with the scheduled walk-out!

Chief Harrington assured us he supported our efforts and even implored us: “Next time you plan to do something like this, please let me know ahead of time…”

“You would let us barricade the building?” someone off camera asks dubiously.

“Oh, sure, I don’t care,” he claims. If this wasn’t bizarre enough, Harrington then went so far as to offer to set up a sound system for us in the nearby amphitheater for the strike!

In a surprise turn of events, we walked from Milneburg Hall not in handcuffs but with fists raised, into the triumphant cheers of supporters! We took an hour to regroup ourselves before the walk-out commenced. Our still-born occupation may have been thwarted, but there was still hope for a strong strike. At 10am 200 students skipped class to gather in the quad. In the distance hung a banner, dropped guerilla-style days earlier, reading “Become the crisis. Strike against the budget cuts” off the side of the Liberal Arts building. Students who felt the urge took the megaphone to voice their opposition to the tuition hikes, class and graduate program cuts, the limited entrance scholarships and the laying off of faculty. Students pointed out that Louisiana is 48th in education in the nation, and how this further scourge on higher education will only exacerbate crime and poverty in New Orleans. How the state spends more on incarceration than it does on education. How those at the top of the pyramid still make their six-figure incomes while janitors—given only crumbs to begin with—are being laid off.

The unpermitted rally was obliged to move from the quad to the amphitheater in order to appease the police. As we migrated across the campus, the crowd decided that a quick detour through the administrative building was appropriate. Thus, students could tell the chancellor directly how they felt. A protest out in the quad is easy to ignore; inside his office…Not likely!

Without any leaders or formal organizing body, the students had taken it upon themselves to disrupt the university. As we approached the Admin building, a lone, bone-headed officer stood sentry at one of the glass doors and attempted to block the path. To no avail: the crowd simply opened the adjacent door and strode past! A sense of accomplishment possessed us as our chants reverberated through the halls. When the kids up front began to gridlock the stairwell, a quick consensus was reached. “Up the stairs!” they yelled.

Wall to wall with banners and bodies, the crowd snaked its way through the hallways, cheered on by the excited secretaries. Then out came the goons to spoil our fun. “We’d like to speak with the chancellor,” one of us piped up to the clustered line of cops suddenly blocking the way. “He’s not in” is all the answer we received. Just then our “buddy” Harrington gave his dogs the order to “clear the building,” and a few cops unleashed their batons and began swatting at the large group. In their lashing buffoonery, a club made contact with a dispersing student’s calf.

The confused student who’d been struck turned around to face his assaulter—only to be pounced upon by multiple cops! Another student was attacked and pepper-sprayed for simply taking out his camera phone! Apparently, the cops wished no outside eyes to witness their brutality. But witness it they did: in the stairwell, as captured by WWL-TV, Harrington can be seen blustering down the stairs like a veritable mall cop who’s suddenly found himself doing security detail in Tahrir Square. The police aggression culminated in Harrington dragging a student along with him in a headlock. A chorus of Let him go! resounded from the throng of students, as Harrington and his men fruitlessly fought to maintain order.

It doesn’t take much for a New Orleanian to decide the police have gotten out of line, and students were quick to discard the cops’ claims to authority, quickly “unarresting” their beleaguered classmate from Harrington’s clutches. Anarchy, it appeared, was upon us! As word spread that a comrade had been pepper-sprayed, the crowd enfolded the cops who were dragging the poor distraught soul in handcuffs away to a squad car. “I was attacked!” he screamed to the protestors and to the cameras. Only after his girlfriend insisted he be led away for medical treatment (and inevitably, jail) was the police car allowed passage. All in all, two were arrested by the end of the afternoon.

That night Chief Harrington was all over the news, laying it on real thick for the cameras, before being carted away on a stretcher. Watching the news footage one begins to wonder whether the chief shouldn’t have pursued a more respectable career in soap opera: “He punched me in the ribs,” he says, dramatically panting and dabbing his forehead. “Then he pushed me down the stairs and…” (painful sigh) “…that’s when I twisted my ankle.” But reactionary press came as no surprise and made little difference to us. Even if spectators believed the pathologically dishonest New Orleans police and thought the students had initiated the violence that day, it succeeded in demonstrating students were willing to fight against the budget cuts—and indeed, had already begun!

We imagined that September 1st would spark a conflict that would rock the LSU administration’s ranks like the revolutions crumbling the imperialist regimes of the Maghreb. And in some small way, perhaps it did. Just weeks after the protest, UNO’s Chancellor, Timothy Ryan, was fired, along with much of his bloated administration, presumably for their incompetence in handling the unrest on campus. Tim sympathizers rest assured; Mr. Ryan was virtually never on campus anyway (at least one thing the cops said that day was true: he really wasn’t in his office during the rally!); thus, his removal probably wasn’t too drastic a transition.

It soon became clear, however, that Tim‘s firing signified not a reform of the university but a measure to tighten control over it—with John Lombardi, LSU system president, promptly usurping the position of Chancellor. Whereas Tim Ryan was a crook getting rich off his administrator’s salary, he was merely another dirty Louisiana politician. Lombardi, on the other hand, is a foreign invader, a truly reviled autocrat notorious for the continued condemnation of the public Charity Hospital and the destruction of hundreds of homes in Lower Mid City to pave the way for LSU’s new, upper-end medical facility. In a news story, a UNO student confronts Lombardi on his newly conquered campus, asking if he would be willing to take a cut from his 600K salary. Lombardi, in his cream colored suit, impudently sips his diet-coke than turns around and walks away without answering the question. Students calling Lombardi out like this during his infrequent visits to UNO campus have not been uncommon, and hundreds of wheat-pasted posters picturing Lombardi with the ironic caption, “Outside Agitator,” adorn its buildings.

It soon became clear, however, that Tim‘s firing signified not a reform of the university but a measure to tighten control over it—with John Lombardi, LSU system president, promptly usurping the position of Chancellor. Whereas Tim Ryan was a crook getting rich off his administrator’s salary, he was merely another dirty Louisiana politician. Lombardi, on the other hand, is a foreign invader, a truly reviled autocrat notorious for the continued condemnation of the public Charity Hospital and the destruction of hundreds of homes in Lower Mid City to pave the way for LSU’s new, upper-end medical facility. In a news story, a UNO student confronts Lombardi on his newly conquered campus, asking if he would be willing to take a cut from his 600K salary. Lombardi, in his cream colored suit, impudently sips his diet-coke than turns around and walks away without answering the question. Students calling Lombardi out like this during his infrequent visits to UNO campus have not been uncommon, and hundreds of wheat-pasted posters picturing Lombardi with the ironic caption, “Outside Agitator,” adorn its buildings.

Yet, despite the rumblings of revolt, the forces of repression and co-option proved too strong for another uprising; the momentum ultimately dissipated. Now that the ball had begun rolling, the Save UNO coalition, in an effort to capture the movement, moved their tentatively planned protest in Baton Rouge from March up to November. And so began the campaign of bake sales and efforts to bolster public image that drive the movement into the ground with boredom. Try as we might to organize with the Save UNO Leftists, we were instead treated as a threat to their efforts. Rather than merely ignoring our actions as they did for the September 1st action, they swiftly sought to veto our every move, chiding us on how we would destroy their campaign if we planned another strike. Though our body of rebels had nearly tripled since the first week of school, we were demoralized by the “legitimate” organizing body actively obscuring us. At a large public meeting announcing plans for their rally in Baton Rouge, Save UNO feigned ignorance as numerous people inquired about what the organizers of September 1st were planning next. For another of their events, a “block party” put on to garner further support for the Baton Rouge protest, we were bluntly told that we were not allowed to come and hand out fliers.

The deplorable block party incident made clear that Save UNO wanted nothing more than for us to disappear and leave all the organizing to them. The pitiful event itself, however, gave a clear indication of the efficacy of their tactics. There were practically more undercover cops snapping pictures than there were students, as local politically-conscious rapper Truth Universal and his crew serenaded an all-but-empty amphitheater.

But repression was not only coming from the Left. In the fall-out of September 1st, as we scrambled to build support for the initial arrestees, three additional students were arrested at their homes three weeks later by the SWAT team! Abandoned by Save UNO and condemned as the initiators of violence by cowardly professors, public support was scarce. Fortunately the radical scene outside of campus is mighty, and we managed to raise over $500 for legal fees by throwing punk shows. As of this writing, all the arrested students have accepted decent plea deals, reducing their felonies to lighter misdemeanors. But taking these pleas was not at all ideal. Considering the damning footage of police aggression, their cases would have made for promising trials; yet because they possessed little public support, there was no hope for a political defense.

As for the rally in Baton Rouge, we couldn’t have been more opposed. It wasn’t only the contrived feeling of holding an event organized entirely by professors, cops and administrators that was the problem–although after the lucid events that transpired on September 1st this symbolic protest was hard to stomach. We were opposed because we recognized this liberal tactic for what it was: by diverting our attention to higher authorities, they were removing the immediacy of the struggle on campus. Thus the issue became abstract once again, reinstating apathy. Much like the Sacramento protest pushed through by socialist groups at the end of the California university movement, Baton Rouge signified a forced climax to a struggle that still had much left to accomplish. In fact since the rally there hasn’t been a single challenge to the cuts that we can think of.

To conclude, we’ve decided to go ahead and humor that one cynical question impugning every social struggle: “Did it accomplish anything?” Our answer is, of course it did! It wasn’t the “rev,” sure. But does the painter simply pick up the brush and produce her masterpiece with one flourish of inspiration? Would we malign an orchestra for failing to compose its symphony after only the first rehearsal? Well, fomenting social struggle surpasses even these two monumental pursuits: for we must paint the canvas with sweat and blood; we must painstakingly arrange every instrument based on each musician’s talents to create a subversive form! We certainly wished to invoke the spirit of May ’68— nay, the spirit of Greece ’08— for occupations to spread throughout the university, for the students to take to the streets, shutting down business sectors and halting the orderly function of progress. We lament our humble actions did not segue into open revolt in solidarity with burdened workers, the quieted peoples along the devastated coast, and other Louisianans marginalized by capitalism. But remember: it only takes a few initial sparks to ignite the fuse. And our recent adventures have provided us ample practice to hone our skills in this game of social war. Like we said before, victory is in the attempt too, and considering the upheavals looming ahead, we’re looking forward to many more victories…

Share