by M.G. Houzeau

Click here to read part I, “From Self-Sufficiency to Enslavement in the Market.”

They chased, they hunted him with dogs

They fired a rifle at him.

They dragged him from the cypress swamp,

His arms they tied behind his back…

They dragged him up into the town,

Before those grand Cabildo men.

They charged that he had made a plot

To Cut the throats of all the whites.

They asked him who his comrades were.

Poor Saint Malo said not a word!–Creole Slave Song

translation by George Washington Cable

In Louisiana’s rich, mysterious cypress swamps, there is an abundance of fish and game. Indigenous tribes prior to and during early colonization of the area combined a self-sufficient hunting ethic with an agricultural diet of corns, roots, beans and squash– in some ways not unlike many Cajuns and Isleño communities through the present day.

In Louisiana’s rich, mysterious cypress swamps, there is an abundance of fish and game. Indigenous tribes prior to and during early colonization of the area combined a self-sufficient hunting ethic with an agricultural diet of corns, roots, beans and squash– in some ways not unlike many Cajuns and Isleño communities through the present day.

Beyond foodways, however, these swamps exist physically as mazes, difficult terrain for humans to navigate, trace, and document. Their intricate water systems and lush, sprawling vegetation restrict both movement and long-distance eyesight. Thus, these lower Mississippi Valley cypress swamps, known in French colonial times as cipriere, provided a haven, if not quite a heaven, for maroons.

Maroons were enslaved people who’d successfully escaped their “owners.” The term came from marronage, a French word for the act of running away. The tactic of marronage existed along a spectrum: Petit marronage was a short-term leave, usually a few days or a week, that an enslaved person might take, for example to visit a relative at another plantation, while grand marronage meant a permanent attempt at escape, usually to set up a new, free life elsewhere.

In the 18th century a rare confluence of conditions aided maroons in the Louisiana territory, especially near New Orleans. Out on the frontier of imperial power, the colony’s lack of governmental resources allowed people to move about with less official surveillance. Most French land grants on the Mississippi were made in “arpents,” slender river-to-swamp rectangles ensuring river access to every plantation settler. This setup provided enslaved people with a direct route to swamp waterways– the proverbial back door. Over decades, the plain cabin residences along the back cypress swamp sections of many plantations became nodes of a solidarity network between enslaved people, maroons and free people of color in New Orleans.

This network was strengthened through the tangible acts of trading goods, intermarriage and family relations, as well as work exchanges– maroons might do the plantation work of cutting wood while the enslaved would share vegetable produce from their subsistence garden plots. But it was also strengthened through the intangible aspects of empathy, racial solidarity, and creating resistance to authoritarian oppression. Enslaved Africans in the first few decades of French settlement learned about the swamps’ hidden passages and waterways, first from early enslaved indigenous peoples and then from those free indigenous communities that harbored maroons.

Elements of the French and Spanish settler colonial systems provide a further understanding of how maroons and their supporters could create such a strong and vibrant network under imperial noses. While the Code Noir, the French colonial enslavement code, outlawed any sexual relationships with enslaved Africans or Afro-creoles, many French settlers ignored that provision. From these “unions”– the rape of the enslaved by the enslaver– there emerged a growing group of free people of color: not white, but not enslaved.

Consequences of a Colonial Hand-off

In the 1760s, new Spanish rule took over from the local French slave-owning elite and intervened to roll back some of the worst excesses of the French towards enslaved people. Spanish law eased restrictions on movement and, since plantation owners often demanded the enslaved hunt game animals, lightened the laws against enslaved people carrying firearms. The number of free people of color increased due to a broader allowance of manumission, the process by which an enslaved person could pay his or her purchase price in exchange for freedom. Enslaved people were able to save money by doing external contract work once their other work commitments were met, though they could only keep a portion of the proceeds; their “owners” of course took a cut.

The Spanish administration even allowed enslaved people to travel to New Orleans and file claims of abuse against their “owners” in court. In New Orleans, the wide-ranging, regular mobility of people of color, both free and enslaved, made it difficult for authorities to determine who had the right to be where, providing some cover to maroons who had run away from harsh plantation conditions.

Maroon communities were not isolated in the swamps; they played an active part in the Louisiana market economy. Historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s extensive research on Afro-Creoles during the colonial era led her to the conclusion that fewer maroons “continued to raid plantations and kill cattle… [instead] there was a move toward production and trade for economic survival.” (Hall, 203)

During the mid-eighteenth century, the plant-based dye indigo became increasingly popular, increasing demand for the cypress-wood troughs and vats used in its production and export. Maroons in Louisiana occupied an advantageous and unique position: they had access to and familiarity with the cypress swamps as well as experience chopping down cypress trees to build homes. Lumber mills along the east bank of the Mississippi downriver from New Orleans, today’s St. Bernard Parish, intentionally ignored the legal status of their piecework laborers: the drive for profit outweighed loyalty to colonial law.

By the early 1780s, mill operations and maroon communities had a mutually beneficial (if imbalanced) relationship organized around resource exploitation. Maroons were paid per piece of sawed cypress log delivered behind the lumber mill.

This cash economy helped solidify relations between maroons, enslaved people on plantations and those who sold and bought crafts and food at the markets in New Orleans. Spanish authorities began to worry about the “runaways” downriver establishing more permanent maroon settlements like those already in the mountains of Jamaica, Haiti (then St. Domingue), Brazil and Santo Domingo. The colonial powers were deeply concerned by the increasing organization of Louisiana’s maroon communities, and the maroons’ gradual unification behind a leader they called Saint Malo.

The Enigmatic Saint Malo

The name St. Malo is interesting. Malo means bad in Spanish…Malo means shame in Bambara and refers to the charismatic leader who defies the social order, whose special powers and means to act may have beneficial consequences for all his people when social conventions paralyze others.

– Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana

The maroon leader Saint Malo, known as Juan Malo while enslaved, was widely respected even among enslaved creoles who stayed in their homes and did not brave life in the swamps. Those who wrote the official histories of that time didn’t include his voice; we know of his existence only through statements in colonial archives made by captured maroons, folk stories in Afro-Creole communities, and a highly suspect “confession” attributed to him.

When slave trade to Louisiana experienced a resurgence in the 1780s, slave control became a top colonial priority, and funding went towards immediately curtailing the dangerous autonomy of maroon communities. Plans and raids directed from the highest Spanish authorities began in 1781. Though the general area of St. Malo’s hiding place in the cypress swamps was known to Spanish authorities by 1782, it proved difficult to locate precisely.

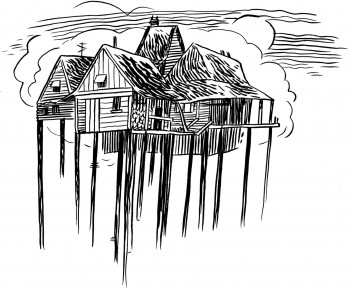

Unable themselves to find St. Malo in the labyrinthine swamps, colonial authorities changed tactics and sent a trusted enslaved Afro-creole as a spy to infiltrate the maroons. The spy reported back that Saint Malo’s basecamp, a small settlement of a few wooden cabins, would be nearly impossible to raid successfully because the narrow, intricate backwaters leading to it prevented one from using boats of any kind. Instead, the militia would have to wade in chest-deep water, holding their guns over their heads. While St. Malo lived mostly at a farther settlement at Chef Menteur, he had always moved freely among various settlements to keep up relations among maroons and organize their defense. When a colonial raiding party finally made it to the purported settlement in 1783, most of the maroons escaped– only one died and twelve were taken alive.

Through the arrest of other maroons, the Spanish authorities found a strong family and relational network of free and enslaved peoples of color. To divide these ties and increase the pressure on maroons’ access to resources, the Spanish Governor proclaimed in May 1784 that all free people of color would be held responsible for the “crimes” perpetrated by the maroons– theft of food surely, but mainly the maroons’ “thefts” of themselves and their labor from their “owners.” This proclamation heavily restricted the movement of enslaved people and banned trade of any kind with the enslaved, and added restrictions on hunting to prevent the enslaved from being armed.

This pressure had an impact on the maroon communities. A dispute between formerly symbiotic enslaved and maroon groups along one of the plantations downriver of New Orleans escalated, ending with the plantation’s enslaved people turning in a maroon to Spanish authorities. St. Malo and his band, cut off from essential information and supplies, reacted by retreating deeper into the swamps. The Spanish increased the rewards for breaking solidarity: bringing in a maroon or giving information leading to a maroon’s capture guaranteed the snitch his or her own freedom and a significant monetary reward.

By early June 1784 a raiding party of ninety soldiers was established to both pursue St. Malo and cover his potential escape routes along the edge of the bayou near Lake Borgne. In most militias, including the force which put down the indigenous revolt at Natchez in 1730, the troops were a mix of free blacks, enslaved people and white working-class soldiers, and the commanding officers were ruling-class whites. That was true of this raiding party as well, with the exception of Captain Bautista Hugon, a free man of color– the man who captured St. Malo.

On June 14, 1784, the militia captured forty maroon men and women, including a wounded St. Malo. Without even a pretense of trial, he was hanged five days later along with many of his fellow resistance leaders. Although St. Malo’s supposed “confession” of a plan to overthrow the colony was was accepted in private by a colonial judge, no evidence of it ever surfaced. If it existed, such a plan would necessarily been by word of mouth, and most maroons, as St. Malo in the song, said “not a word.”

The Limits of Defensive Resistance

There has been long historical debate about the revolutionary potential of maroon communities. Part of the debate has rested on historians’ racist assumptions when reading the documentary evidence. Until recently, historians rarely considered the power dynamics at work between the colonial administrators, the maroons and the authoritative construction of an official public text. Historians of slavery imbued maroons only with enough agency to escape from servitude and establish new settlements, but not with the conscious exploration of further resistance to bring down the institutional system of slavery. This lack of explicit revolutionary fervor on the part of maroons was described in, for instance, Brazil and Jamaica, where long-term, stable maroon communities existed in the 18th and into the 19th century.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1803) put to rest any notions of slavery’s inevitability or invincibility. Just seven years after St. Malo’s murder, enslaved Africans with the assistance of hundreds-strong guerrilla maroon communities from the mountains began targeted riots and a military overthrow of the French colonial system in St. Domingue (today’s Haiti).

In a historical wink, a coincidence perhaps, one of the injured leaders associated with St. Malo in the 1784 destruction of the maroon community was turned over and resold to an unsuspecting slave owner in St. Domingue. What happened to this driven, passionate leader? St. Domingue was so brutal that the average enslaved African there survived only seven years; did this veteran live to see the revolution?

For Louisiana’s history, questions such as these reflect the transnational nature of early New Orleans culture. With the success of both the French and Haitian Revolutions, new radical influences came into circulation. These revolutionary ideas of attaining freedom via a violent restructuring of society are in sharp contrast to the violence of 1780s Louisiana, which flowed solely downhill– from white plantation owners and colonial authorities to the enslaved and free people of color.

Despite their causing disruptions to the economic profitability of the slave system, Louisiana’s maroon communities never attacked Louisiana colonists. Any violent confrontations had been “almost entirely defensive” from the maroons’ standpoint. (Hall, 226-227)

This failure of defensive resistance and the successes of revolutions elsewhere made an impression on our region’s enslaved and maroon Afro-Creole organizers heading into the 19th century. Instead of shedding their chains for subsistence and seeking autonomous lives in the swamp, Louisiana’s movements of resistance began to look toward the more direct and confrontational action of revolt.

Cable, George Washington. Cajuns and Creoles: Stories of Old Louisiana (Doubleday, 1959)

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: the Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Note: much of the historical material—rather than analytical material—come from Hall’s incredible work. Other sources were also considered, including:

Din, Gilbert C. Spaniards, Planters, and Slaves: The Spanish Regulation of Slavery in Louisiana, 1763-1803. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999.

Powell, Lawrence N. The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Share